Beauty and the Blue Crab

Something mysterious about Rupert stops Charlie from his routines of psychiatry, but what is it?

As the story unfolds, the answer becomes more and more complex, but one part is that Charlie believes he’d be killing something beautiful. Charlie is baffled—he’s a scientist and beauty shouldn’t have anything to do with his treatments—but it becomes clear that this mysterious beauty relates to more than Rupert’s piano playing. It touches the whole of Rupert and brings Charlie to an existential crisis.

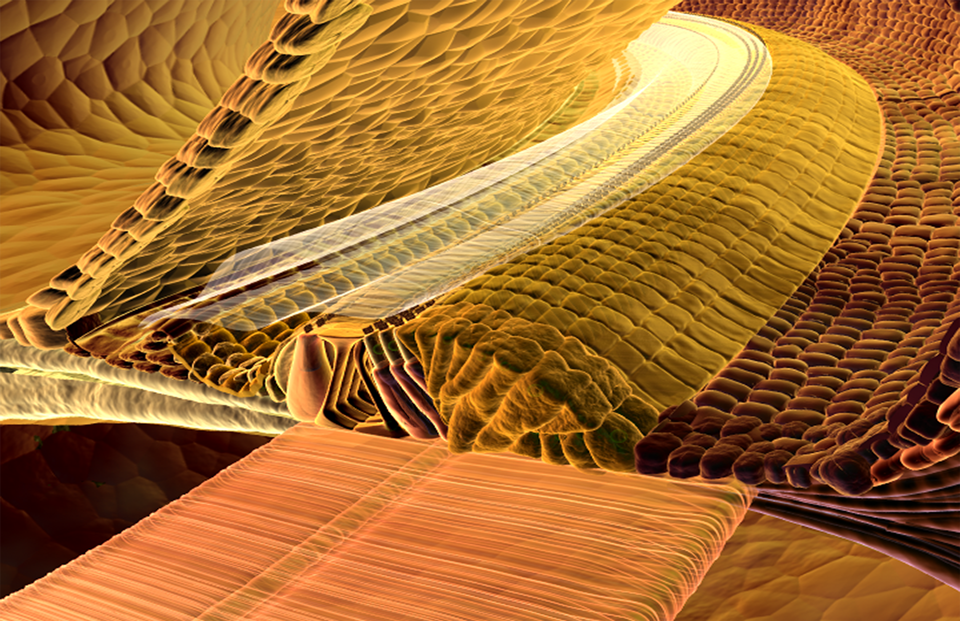

Late one afternoon while attending college, I read Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, his famous novella written around the dawn of the 20th century. I had just read a paragraph and noticed the unusual beauty of the mental image. I savored its high resolution, saturate color, and three-dimensional depth—all with exceptional clarity—and the brilliance of image showed no sign of diminishing in my mind. In that moment, my love of literature blossomed.

I decided to write my own paragraph describing the same image. I shut the book and worked hard on it, imagining myself in Conrad’s mind, looking at the blank sheet before him. After a long while, pleased with my finished paragraph, I re-opened Heart of Darkness and placed Conrad’s paragraph next to mine.

I was shocked. His paragraph was so powerful and mine so pale that I was truly embarrassed sitting alone at my desk. It was a great lesson in how ignorant I could be and how masterful Conrad was. But I was also enchanted by the grace in his words. I saw how much style—an abstraction separate from the content—could contribute to meaning. I particularly noticed how the arrangement of his clauses within the sentences and of sentences within the paragraph—guided the image smoothly into my mind.

In one sentence, for instance, he wrote an independent clause, followed by a series of dependent clauses, each elaborating on the independent clause:

A__a1__a2__a3__a4

I was a music major in college and was struck by how much this pattern reminded me of a Bach fugue, in which Bach would state the main theme and follow it with fragments.

Theme__fragment1__fragment2__fragment3__fragment4

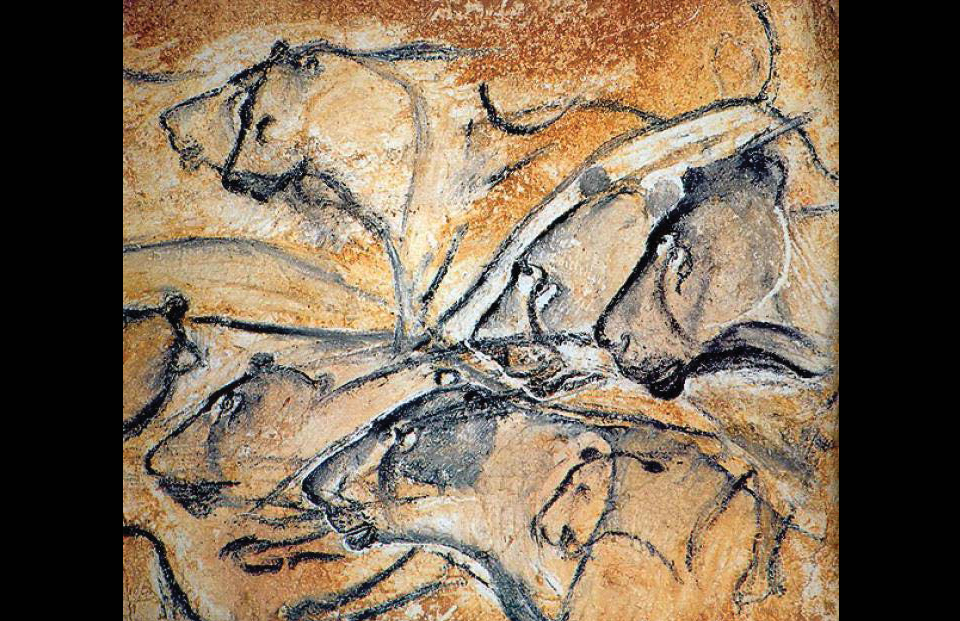

At the time, I was also reading Gregory Bateson, who pointed out similar patterns in nature. In a crab, for instance, the large frontal claws protrude like a main theme that is repeated in the smaller legs.

Claw__leg1__leg2__leg3__leg4

Because the main theme is followed by variations that elaborate the main theme, I thought of this pattern as repetition with variation and elaboration.

With Conrad’s paragraph, Bach’s fugue, and the blue crab in mind, I began to see this pattern everywhere in enduring works from our human history: from the columns in the Parthenon to the arches in the Alhambra; from the rhythms in Shakespeare sonnets to the inverted pitches in Beethoven’s late string quartets; from the round dabs in Monet’s water lilies to the rounded corners of Apple’s iMac. And like the crab legs, I saw this pattern everywhere in nature: in the arms and legs of horses, humans, and frogs; in the tentacles of jellyfish; in the branches of trees.

As Bateson points out, we see this pattern in living things or in the artifacts of living things, but not in mountain rocks or non-musical sound waves.

What if our response of beauty, even crudely, or even partly, is our vague recognition of things from the world of life?

Baxter asks Charlie why natural selection would keep beauty in the genetic game. Why keep the physiological responses?

We can speculate: it would have been invaluable to our ancestors to distinguish—at a glance—whether something was from the world of life or the world of non-life. Survival could be at stake.

Could this mean Conrad tailored his words to resemble patterns found in life? Was he hijacking our rails of perception that are hardwired in our nervous systems to notice this (and other) pattern and generate physiological responses, as part of his art? And did my paragraph fail because it resembled no such pattern?

I am impressed to this day, thirty years later, that I still see the rich image that Conrad lit up in my mind. If an MRI machine had been scanning my brain back then, I am certain the nooks and crannies of my brain would have lit up wildly in color.

Maybe this is what happened to Charlie when listening to Rupert talk about his hallucinations.